Written by Martin Russell,

In the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, World Aids Day on 1 December is a timely reminder of the need for continued efforts to tackle other global health problems. Since the first cases were recorded in 1981, the disease has claimed 33 million lives worldwide. New infections and deaths are steadily declining but there are still huge disparities and challenges to meeting the UN target of ending the epidemic by 2030.

Global and regional trends

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) is transmitted through blood, semen, as well as vaginal and other bodily secretions. Infections spread through sexual intercourse, sharing of needles by drug users, and sometimes through blood transfusions. Mothers can also infect their children during pregnancy and breastfeeding. If left untreated, HIV attacks the body’s immune system, and may lead to AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). Due to their loss of immunity, most AIDS sufferers die within a few years due to contracting other severe diseases such as tuberculosis and cancer.

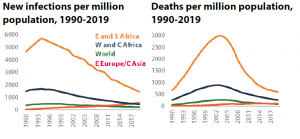

HIV is thought to have originated among central African primates. Human infections were first identified in the United States in 1981. In most parts of the world, the epidemic reached its peak around the turn of the century. In southern Africa, the worst affected region, AIDS caused average life expectancy to plunge by nearly 20 years in some countries. Since then, both infection and death rates have declined steadily. In 2019, there were an estimated 690 000 AIDS-related deaths (-59 % compared to the peak in 2005) and 1.7 million new infections (-39 % down on the 1999 peak). The total number of people living with HIV is 38 million.

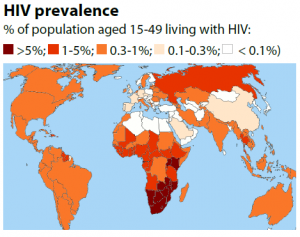

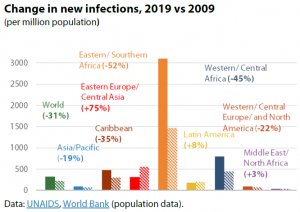

HIV is most prevalent in eastern and southern Africa, where nearly 7 % of adults are living with the virus. This percentage reaches over 20 % in southern African countries such as Eswatini (27 %), Lesotho (23 %) and Botswana (21 %). However, this is also the region that has seen the biggest progress in terms of curbing new infections (-52 % since 2009). Though starting from a much lower level, new infections in eastern Europe and central Asia are rising fast (+75 %). Certain groups are much more severely affected than others. Although they only represent a small share of the population, gay men, drug users and sex workers, together with their clients and partners, account for the majority of new infections in all regions except for eastern and southern Africa. Although infection rates are mostly similar for men and women, in many African countries young women are far more likely to catch the virus than men.

Progress towards curbing the epidemic

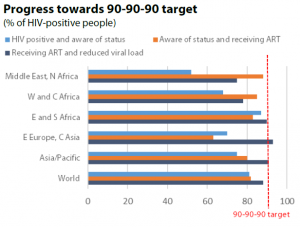

The sustainable development goals adopted by the UN in 2015 envisage ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2030. In 2014, UN agency UNAIDS set three intermediate goals for 2020: at least 90 % of people with the virus should be aware of their status; of these, 90 % should receive treatment, with virus levels in 90 % of patients receiving treatment reduced to a level where no infection is possible. The combined effect of achieving these three targets would be to cut infection rates by three-quarters. Southern and eastern Africa, the worst affected region, has come close to achieving these targets (87 %; 83 %; 93%), helping to explain the dramatic drop in infection rates, while the eastern Europe/central Asia region is one of the worst performers (70 %; 63 %; 93 %), figures that again correlate with sharply rising infections.

No cure exists for HIV/AIDS, but it can be managed as a chronic disease through antiretroviral treatment (ART), which reduces concentrations of the virus in the body to a level where it no longer threatens the patient’s life or infects others. The same drugs can also be taken preventively by persons who are at high risk of exposure (such as sex workers). ART is expensive, not least due to the fact that it has to be continued through a patient’s entire remaining life, but also highly effective; the experience of Brazil, which has provided ART free of charge since 1996, demonstrates that universally available treatment is affordable even for middle-income countries. However, 13 million HIV-positive people (one-third of those infected) do not yet have access to it. Prevention also plays an important part, for example, sex education, encouraging the use of condoms, and circumcision for men – which reduces the risk of female to male infection by half.

There are still many challenges

UNAIDS points to a funding shortfall: in 2019, US$18.6 billion was available to tackle the disease in developing countries, 7 % less than in 2017 and 30 % less than the UN target of US$26.2 billion. Declining funding may reflect complacency, as infection rates have been dropping in most countries. Funding will be even scarcer in 2020, with healthcare resources diverted to tackle the coronavirus pandemic. Covid-19 obstructs the fight against HIV/AIDS in other ways, for example by disrupting medical supply chains or discouraging patients from leaving home to seek treatment. The persistence of the HIV epidemic points to wider social and behavioural issues that cannot easily be addressed through drugs and funding alone. Some religious groups oppose condoms, arguing that they encourage promiscuity – an obstacle to efforts to promote safe sex. In Russia, there is strong resistance to introducing sex education in schools, while NGOs that distribute free needles and condoms to drug users are also frowned upon. Conservative attitudes are part of the reason for Russia’s high and rising infection rates. Many countries are unwilling to take steps, such as legalising prostitution or treating heroin addicts with methadone, which could protect some of the most vulnerable groups. In some Middle Eastern countries, nearly 90 % of the population has negative views of people living with HIV. Stigmatisation can discourage patients from seeking treatment, and may even result in them being denied healthcare.

Leading the global fight against the epidemic

Established in 1996, UNAIDS took over from the World Health Organization as the lead UN agency responsible for coordinating the fight against HIV/AIDS. It has played a key role in curbing the spread of the disease by raising awareness and mobilising resources. However, many observers question the value of having a separate body from the WHO, arguing for a more integrated approach that helps developing countries tackle health problems across the board; they also point out that HIV/AIDS receives a disproportionate amount of funding compared to threats such as diabetes, which claim far more lives.

Through its PEPFAR fund (US$6.9 billion in 2020), the US is the main foreign contributor to spending on HIV/AIDS in developing countries. The EU does not have a dedicated HIV/AIDS programme, but in 2019 it pledged €550 million over the next three years for the Global Fund, a UN-led partnership to tackle HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. Since 2014, the EU has also allocated €220 million from the Horizon 2020 programme for HIV/AIDS-related research. In 2017, the European Parliament called for an integrated EU policy framework on HIV, tuberculosis and viral hepatitis.

Read this ‘at a glance’ on ‘The Global HIV/AIDS epidemic‘ in the Think Tank pages of the European Parliament.

[…] […]