Singapore also took quick action, closing its borders, extensively testing and tracing infections. Until March 2020, this approach seemed to be containing the spread of the disease without the need for an economically damaging lockdown. However, the crowded dormitories, which are home to over 300 000 migrant workers and make social distancing physically impossible, proved to be the city-state’s Achilles’ heel. Faced with a surge in new cases, in April the government finally imposed a ‘circuit breaker’ lockdown. With just 5 million residents, Singapore has outstripped its more populous neighbours, and now has the highest infection rate in the region.

However, this seemingly gloomy picture needs to be put in context: the high number of confirmed cases has to do with the fact that Singapore has tested far more extensively than any other country in the region (in Brunei too, widespread testing correlates with high infection rates). New daily infections among Singapore’s migrant workers remain high, as it systematically tests every single dormitory resident. Meanwhile, in the wider community outside the dormitories, the spread of the disease has been halted, with almost no recent new cases among citizens or permanent residents. At no point has the healthcare system been overwhelmed. So far, Singapore has had just 24 deaths, a mere 0.07 % of confirmed cases – after Qatar, the lowest mortality rate of any country with a statistically significant number of infections – compared to 10 % or more in most European countries (this low figure partly reflects the fact that most infections were among the relatively young migrant worker population). The country is investing in research into tests, and its Bluetooth-based contact tracing app has inspired similar solutions in several countries, including Australia.

Unlike Vietnam and Singapore, most other south-east Asian countries were initially complacent. Leaders cited tropical heat, in Indonesia, and traditional lifestyles, in Myanmar, as factors that would slow the spread of the disease. For Philippine President, Rodrigo Roa Duterte, there was ‘nothing to be extra scared of’. Governments dragged their feet over introducing restrictions: in Malaysia, a religious event attended by 16 000 Muslims in late February was allowed to go ahead, enabling the virus to take hold. During the same period, a political crisis toppled the government, further handicapping the country’s response. In Thailand, the government’s decision to impose a lockdown resulted in a huge exodus from Bangkok, spreading the virus to the provinces and neighbouring countries.

While other countries closed their borders, Indonesia announced a multi-million dollar social media campaign to attract foreign tourists. It was also slow to restrict internal travel; for weeks, the government dithered over whether to ban the annual mudik exodus, which sees tens of millions of Indonesians returning from cities, such as Jakarta, to their home towns and villages to celebrate the end of Ramadan. The decision to do so was not taken until late April, by which time many had already left, spreading infection across the country.

Despite initial blunders, both Malaysia and Thailand have managed to contain the epidemic, which is now on a clear downward trajectory. Malaysia brought in strict quarantine measures; isolation of infection hotspots and general restrictions on internal travel helped to stem the virus. In both countries, many observers credit health ministry officials and medical professionals, rather than governments, with turning the crisis around.

By contrast, infection rates remain stubbornly high in Indonesia and the Philippines; with low testing rates in both countries, the real number of cases is probably even higher – perhaps even three times higher in Indonesia. Restrictions are often poorly enforced: in Indonesia, a survey found that only one-third of companies complied with social distancing measures for their employees, while thousands evaded travel restrictions by hiding in lorries and bus luggage compartments. Some parts of the country have resorted to measures such as punishing quarantine violators by publicly shaming them on social media, sentencing them to community service or even forcing them to sleep in haunted houses. Although the epidemic shows no sign of running out of steam, the Philippines has partially lifted its lockdown, and Indonesia is preparing to do likewise.

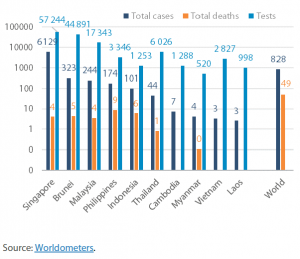

It could hardly be argued that Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar, which are the three poorest countries in the region, have taken very effective measures. For example, communities in Myanmar have been left to their own devices in fighting coronavirus. Nevertheless, very few infections have been reported. To some extent, this probably reflects very low testing rates, and perhaps also deliberate under-reporting. At the same time, there are no signs of a major healthcare crisis of the kind seen in some European countries anywhere in the region. All 10 countries are below the global average for coronavirus mortality, and only Singapore exceeds the global average for the per capita infection rate. Although the impact of heat and humidity on the virus is disputed, only a few of the world’s worst affected countries are located in the tropics. In the less developed countries of the region, there are additional factors that slow the spread of infection, on such being that a large share of the population lives in rural areas and is also less likely to travel extensively.

I wish to point out that you have mistakenly put Thai test in the table at 6,000 is very wrong. As of May 2020 Thailand have already rested over 200,000. “The average age of the accumulated patients was 39, he said. The numbers of provinces with and without new cases in the past 28 days is now equal at 34. More than 200,000 tests for the pathogen have been administered.” As of May 2020 https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1912932/thailand-logs-1-new-covid-case-no-deaths-tuesday I really don’t know how you came up with that small figure.

Dear Nawaponrath,

The graph shows the number “per million of population, as of 2 June 2020”. Therefore, the number of 6000 must be put in the context of the total population of all the stated countries.