Written by Agnieszka Widuto

The economic and financial crisis has significantly reduced banks’ lending to businesses. This gap in financing, coupled with the rise of social media and interactive online platforms, has contributed to the increased popularity of crowdfunding as a possible alternative source of funding. In this context, the European Commission adopted a communication on unleashing the potential of crowdfunding in the EU, as part of efforts to improve the long-term financing of enterprises and encourage innovation. The fragmented nature of the regulatory environment on crowdfunding across Member States may, in certain cases, however, pose challenges to such efforts.

What is crowdfunding?

Crowdfunding usually refers to ‘open calls through the internet to the wider public to finance specific projects’. It typically involves collecting small contributions from a large number of individuals through an online platform. The method was initially used to fund social and creative projects, but has recently expanded to various types of business projects, including start-ups. In 2013, the European crowdfunding market was estimated at €1 billion. This funding volume is lower than retail banks’ lending to non-financial institutions (€6 trillion in 2011), but it is promising compared with other channels, such as venture capital (€7 billion) or business angels (€660 million, visible market segment only). The market is also characterised by fast growth, with some of its sub-segments (e.g. peer-to-peer lending) doubling each year in size.

| Crowdfunding – How does it work?

Crowdfunding connects those willing to give, lend or invest money, with those in need of funds for a specific project. Project owners may be private individuals or businesses. Calls for funds are usually published on an online platform and often promoted on social media. Campaigns include a clearly defined target amount and deadline date, a project description and often a pitch video. Contributions may start from a few euros up to a determined cap, while average target amounts for a single campaign range from €500 (donations – the most frequently used model of crowdfunding) to €50 000 (equity). Project owners can either accept any amount that has been offered, or keep it only if the funding goal is reached. There are currently over 200 crowdfunding platforms in Europe. |

Types of crowdfunding

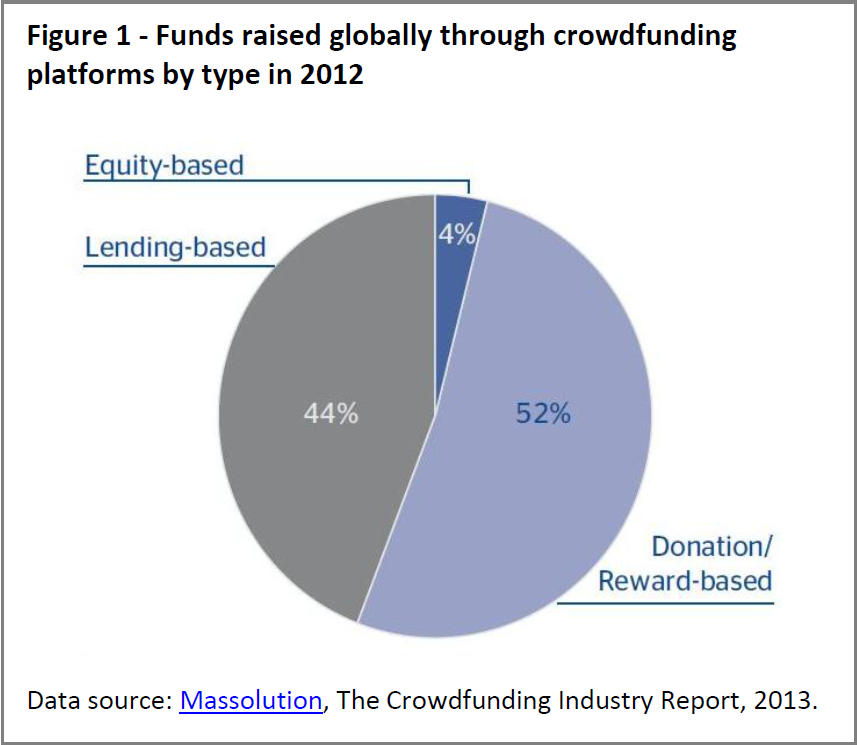

Finance through crowdfunding can generally be divided into two types: with and without financial returns. The non-financial models include donations or rewards. This means that the funders either expect no return or receive a non-monetary reward, often of symbolic value. Some typologies also include pre-sales, whereby contributors pay to develop and produce a new product that will be shipped to them later. The models offering a financial return include lending and equity crowdfunding. The lending model involves individuals providing funds in return for repayment of a loan (with or without interest), while the equity model entails shareholding or profit-sharing. Currently, crowdfunding with non-financial returns prevails and at US$1.4 billion represents over half of the funds raised through crowdfunding platforms in 2012 (see figure 1 overleaf). However, financial-return crowdfunding is expanding as well. Each type follows a different logic, and is potentially subject to a different set of rules.

Benefits and risks

Crowdfunding can improve SMEs’ access to finance and potentially remedy certain market failures, such as the insufficient supply of funding for start-ups and early-stage companies. Its particular design offers flexibility, cost-effectiveness and a high speed of raising funds. Entrepreneurs also gain a market-testing tool which allows them to estimate demand and gather feedback from potential customers. Benefits for contributors include civic or community engagement and, in the case of models with financial returns, an investment opportunity. In more general terms, as SMEs account for a large majority of EU businesses and jobs, the Commission estimates that crowdfunding has the potential to foster growth and job creation.

While crowdfunding can be a financing option for SMEs, it also entails certain risks. These include the risk of fraud, platform closure or failure, project default, cyber-attack, donor exhaustion, misleading advertising practices, legal uncertainty stemming from different legislation, liquidity risk (lack of exit options), and infringement of intellectual property rights. Some of these issues have already been addressed in a number of countries through regulation.

Crowdfunding in the EU

The European Commission recognised the potential of crowdfunding to complement traditional financing channels and indicated its intention to support it in its 2013 Green Paper on Long-term Financing for SMEs. A public consultation with stakeholders carried out later the same year fed into the communication on crowdfunding published in March 2014. While the Commission does not currently envisage taking legislative measures, it aims to explore the added value of EU action. This includes raising awareness, creating a European ‘quality label’ for platforms and developing best practices, notably through setting up the European Crowdfunding Stakeholder Forum, as well as assessing the EU and national regulatory frameworks.

The Commission also sees interest in exploring the possibility of matched (public and private) financing through crowdfunding, at both EU and national levels. Successful examples of supplementing public funds through this new financing form exist. Some possible future options include co-investment in projects alongside private contributors, loan guarantees to crowd-lending transactions, or direct contributions to crowdfunding platforms. Compliance with the state aid and competition rules must be ensured, especially regarding risk finance investments, transparency and accountability, as well as with the EU’s Financial Regulation, where applicable.

At present, regulations vary from country to country, from comprehensive to unregulated. At EU level existing rules could already be applicable to crowdfunding activities, especially those types aimed at providing financial returns, depending on the specific business model used. These rules include, among others, provisions related to financial transactions and payment service providers or intermediaries (Anti-Money Laundering Directive, European Payment Services Directive), protection of intellectual rights (Regulation on Unitary Patent Protection), consumer protection (Unfair Contract Terms Directive, Unfair Commercial Practices Directive), electronic commerce (e-commerce Directive) and investment (Prospectus Directive, MiFID, CRD IV, AIFMD). As crowdfunding has cross-jurisdictional implications – unless investors are to be limited by national boundaries – convergence of national regulatory approaches might also be an appropriate measure.

| During the 2009-2014 legislative term, Members of the European Parliament asked several questions on crowdfunding, urging the Commission to take action in this area. Their main concerns were over clarifying and devising rules on crowdfunding, ensuring a level playing field across EU countries, and protection of consumers and investors. Parliament’s 2013 Resolution on access to finance for SMEs emphasised the importance of diversity in modes of finance and its 2014 Resolution on a hospitable environment for enterprises, businesses and start-ups, pointed out the benefits of crowdfunding in providing investment for SMEs. Crowdfunding was also mentioned as a desirable innovative funding source in the 2012 Resolution on the Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan, the 2012 Report on the programme for the Competitiveness of Enterprises and SMEs (2014-2020), as well as the 2013 Resolution on promoting the cultural and creative sectors. |

Be the first to write a comment.