Written by Denise Chircop

Erasmus+ is the new single integrated European Union education programme for 2014 to 2020 aimed at improving young people’s skills and employability. It also promotes modernisation of education and training in Member States, by facilitating transnational contacts amongst different players and across different sectors. The programme brings together the previous EU programmes in education, training and youth, introduces a loan facility and includes sports as a new area.

Objectives and focus

Overall, Erasmus+ is intended to contribute towards the EU’s strategic objectives for education and training, in line with Europe 2020 priorities, with special focus on addressing skills deficits and skills mismatch. In January 2015, nearly 5 million young people (under 25) were unemployed in the EU, yet a third of employers find it hard to recruit staff with the necessary skills. In this context, Erasmus+ focuses on increasing attainment in higher education, lowering early school drop-out rates and improving attainment in key skills such as knowledge of a foreign language. It seeks to bridge formal (schools, universities), non-formal (evening classes, clubs) and informal (voluntary work) education by supporting certification tools so that skills recognition is not limited to school certificates. This is important as young people who have developed relevant skills following a variety of learning paths and who have studied or trained abroad are twice as likely to find work compared to others who lack similar experiences, and their unemployment rate five years after graduating is 23% lower.

Beneficiaries

Participating countries fall under two categories: programme countries and partner countries. In addition to EU Member States, the group of programme countries currently includes Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Turkey. These countries were required to meet certain conditions and set up a National Agency to manage the programme. Other countries from around the world can become partner countries, with limited access to the programme, on the basis of bilateral agreements.

In programme countries, members of accredited institutions, their students and staff, can participate in mobility exercises. Accredited institutions include institutions offering higher education, vocational education, training or adult education programmes, schools and youth organisations. Students can study and train abroad for periods adding up to maximum 12 months per degree level (undergraduate, master’s, doctorate). Grants vary depending on costs in the destination country (range: €150-500 per month). A student loan facility will enable master’s students to borrow up to €18 000 at advantageous conditions to study for their degree abroad. However, some stakeholders among student representatives have perceived the facility as a threat to the grants system and suggested that young people would be burdened with debts. Additional support is given to students with special needs or those coming from lower income brackets. These funds can be supplemented by national or regional budgets.

The European Commission estimates that the programme will create mobility opportunities for more than 4 million people, among them 2 million higher education students, 650 000 vocational education and training students, 800 000 lecturers, teachers and other staff, 500 000 young people participating in volunteering or youth exchange schemes and more than 25 000 students will study for a joint master’s degree.

A 2014 study commissioned by the European Parliament indicates that programmes such as Erasmus+ are very effective in engaging European citizens in European integration. However, it points out that relatively few EU citizens become beneficiaries and it is more difficult to reach out to ‘untypical’ participants.

Key Actions

Erasmus+ is built on three Key Actions. The first, Mobility of individuals (63% of the budget) will promote learning opportunities for individuals, within the EU and beyond with a target of 20% student mobility by 2020. The second (28%) promotes cooperation for innovation and the exchange of best practices. Around 25 000 Strategic Partnerships will link 125 000 educational institutions, youth organisations and enterprises. Partners are expected to implement innovative practices, and learn from each other. An additional 3 500 institutions, organisations and enterprises will constitute more than 300 Sector Skills Alliances or Knowledge Alliances. Sector Skills Alliances address skills gaps by adapting vocational education and training to sector-specific labour-market needs. Knowledge Alliances foster innovative and entrepreneurial capacity in higher education. Furthermore, this Action helps higher education institutions to develop their international dimension, including that of partner countries. Support will also go to IT platforms developed as spaces for virtual collaboration. The third Key Action (4.2% of the budget) supports the development of policies. It brings together young people and policy-makers in focused discussions, finances studies and information-gathering and encourages peer learning by means of actions such as the exchange of best practices. It also supports tools such as Youthpass that help mobility by facilitating the recognition of qualifications.

Budget

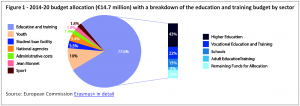

Erasmus+ has been allocated a budget of €14.7 billion for the 2014-20 period, a 40% increase on the previous period but a decrease on the amount originally proposed by the Commission. An additional €1.68 billion is available for actions with third countries through the external action budget. The programme encompasses previous education programmes (notably Erasmus, Tempus, Comenius, Leonardo da Vinci, Grundtvig and Youth in Action) bringing an overall reduction in calls and actions and more efficient use of funds. The division of funds in the three Key Actions described above applies to the areas of ‘education and training’ and ‘youth’. Most of the budget goes towards ‘education and training’ (see figure 1). Within this category, higher education receives almost half of that amount.

Erasmus+ also contributes to sport, which receives 1.8% of the global budget. Funds support collaborative partnerships which promote integrity in sport (such as anti-doping and fight against match-fixing). Grants are also available for non-profit-making European sports events. Sport is also supported by studies and data collection to help policy-makers, and stakeholders’ dialogue, particularly in the annual EU sports forum. Another 1.9% of the budget finances activities under the Jean Monnet sub-programme. These funds are intended to promote worldwide excellence in ‘European Integration Studies’ in higher education by supporting academic institutions, as well as research and teaching activities. Another branch of Jean Monnet activities nurtures dialogue between academics and policy-makers to improve governance of EU policies.

The Commission has published programme guidelines, the work programme for 2015 and is currently issuing calls for proposals. In the meantime, the EP Committee on Culture and Education has expressed concern about the shortfall of payments, amounting to €202 million in the Erasmus+ programme in 2014, which could threaten the programme’s credibility. In practice, grants to students would be disrupted if the budget is spent before year’s end. The situation stems from a deficit in payments in the EU budget which at end-2013 stood at €26 billion, because of the difference in successive years between commitment and payment appropriations. In the adoption of the EU budget for 2015, Parliament pushed to reduce this gap between commitments and payments and secured €16 million more for Erasmus+.

[…] notably digital skills. In terms of specific programmes, a new approach to education and training, ‘Erasmus +, will be put into effect. The programme will cover the period of 2014-20 and offer an additional two […]