Written by Gregor Erbach

A new international agreement to combat climate change is due to be adopted in December 2015 at the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The current climate agreements commit developed countries to take climate action, but not developing countries, some of which have become major emitters of greenhouse gases. After the 2009 Copenhagen climate conference failed to adopt a new agreement, the 2011 Durban conference decided that a new agreement applicable to all countries should be concluded in 2015, and enter into force in 2020.

The 20th Conference of Parties, which was held in Lima in December 2014, concluded with the adoption of the Lima Call for Climate Action, a document that invites all Parties (countries) to communicate their intended nationally determined contributions (INDC) for post-2020 climate action well before the Paris conference.

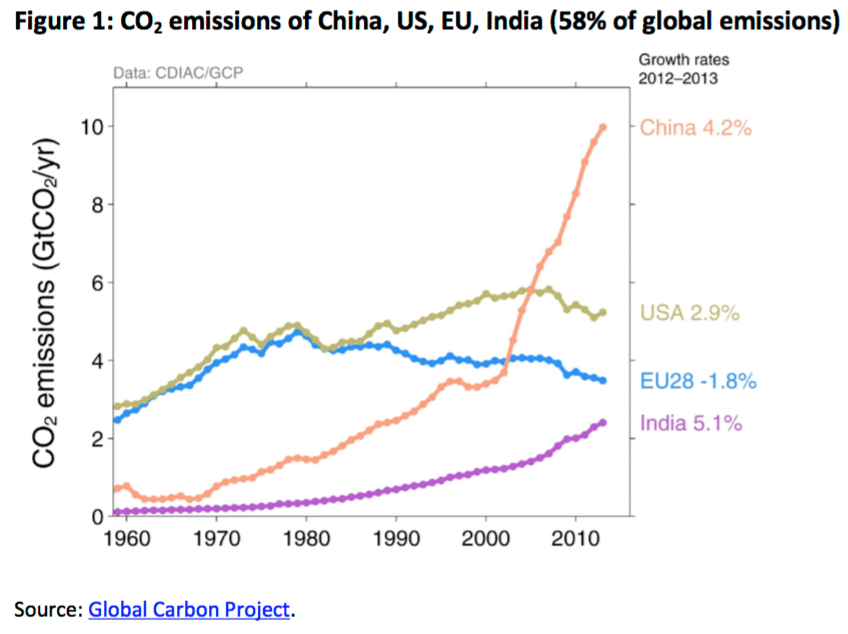

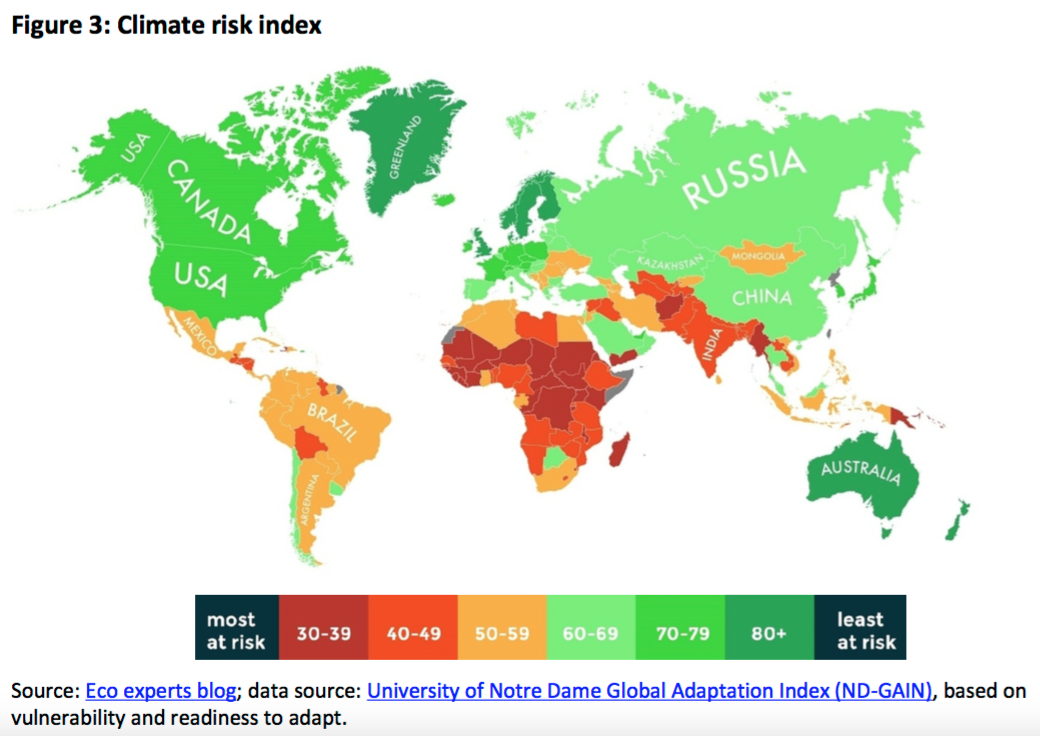

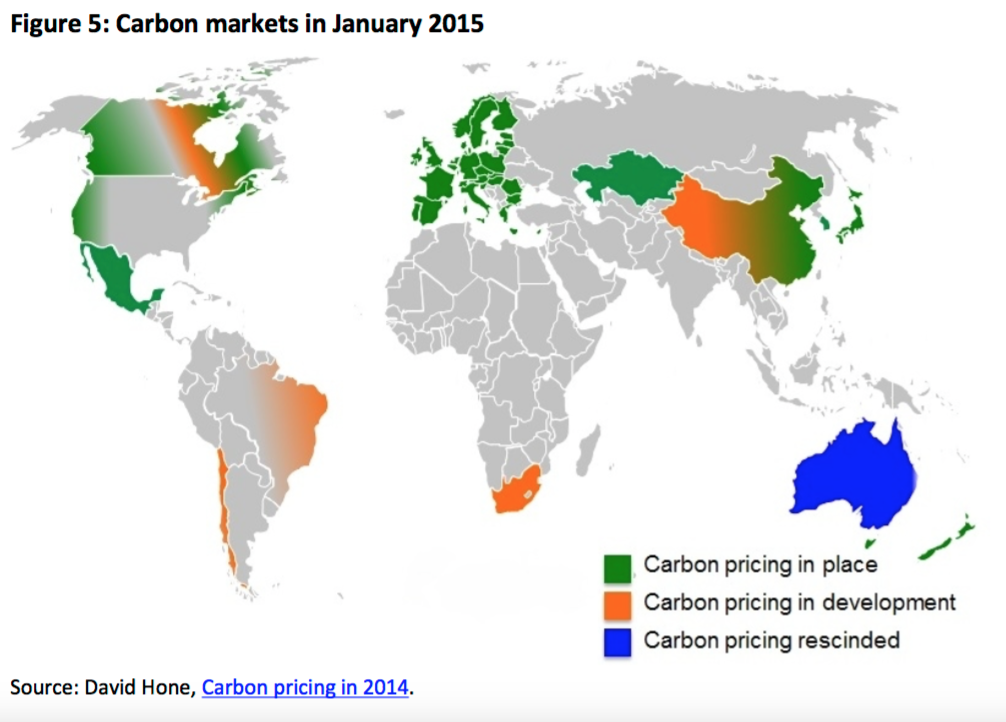

In the course of 2015, the vast majority of Parties submitted an INDC. The EU INDC commits to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by at least 40% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. The US and China – the world’s major emitters – submitted targets that are less ambitious, but still considered as important building blocks to a climate agreement with global reach. Analysis of the submitted INDCs by the UNFCCC secretariat and other organisations found that greater emissions reductions are needed to limit global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, the target agreed in the 2009 Copenhagen Accord.

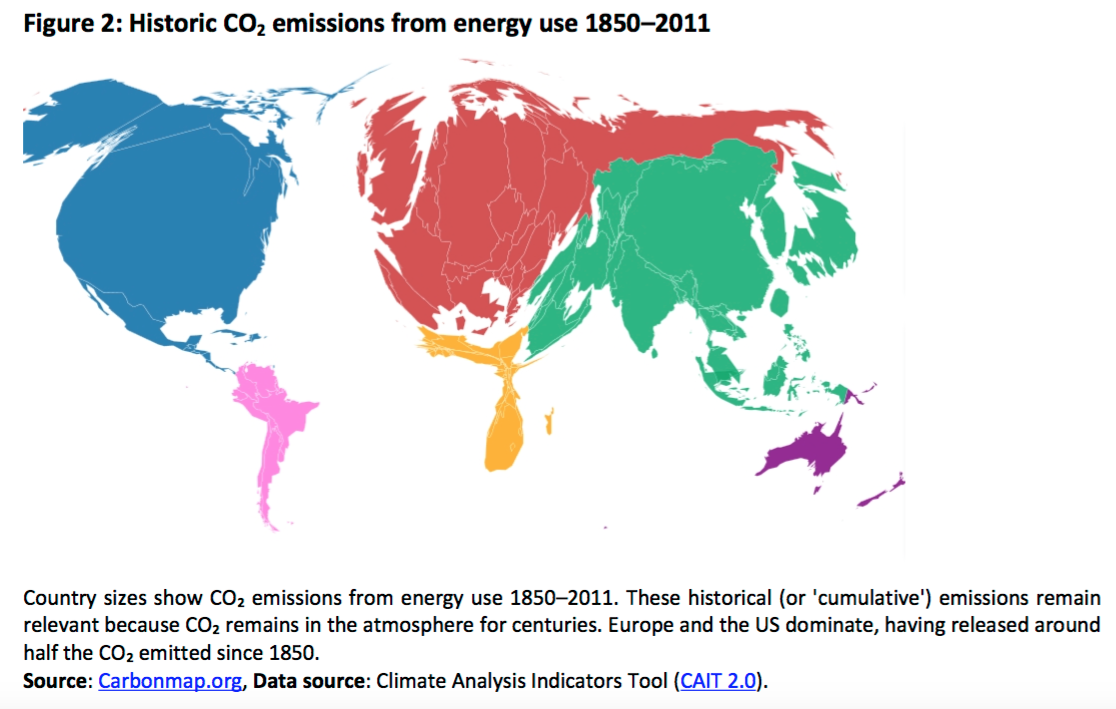

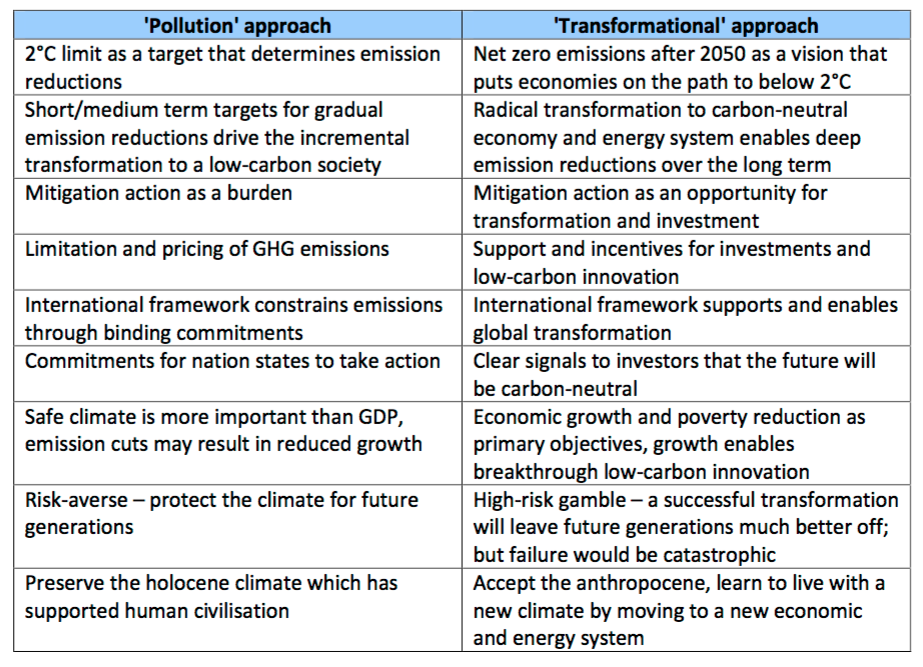

The draft UNFCCC negotiating text from October 2015 leaves a number of important issues unresolved, notably the legal form of the agreement. While some negotiators favour a strong, legally binding agreement, others prefer a bottom-up approach based on voluntary contributions. Moreover, issues of fairness and equity need to be addressed, acknowledging that developed countries have a greater historical responsibility for climate change and stronger capacity for taking action. Processes for monitoring, reporting and verification of national contributions will also have to be agreed. Finally, the question of climate finance is of major importance for developing countries.

The ongoing negotiations present EU climate diplomacy with new challenges as regards shaping the Paris agreement, and once the Paris conference is over, to building collaborations with partners worldwide.

The probable shift from a legally binding environmental treaty towards a ‘soft’ agreement based on national contributions presents both risks and opportunities. Continued engagement with international partners is needed to achieve the transformations in economies and energy systems required to make sure that the risks of global warming remain manageable.

Read the whole In-depth Analysis on ‘Negotiating a new UN climate agreement: Challenges for the Paris climate change conference‘ in PDF.

This is a revised and updated version of a publication from March 2015.

[…] applies to all Parties, but introduces differentiation in responsibilities and capabilities to take developing countries’ circumstances into account. Contrary to previous agreements, the United States has, this time, […]

[…] action from all countries, not just the developed nations. It is the outcome of a long and arduous negotiation process in which the EU played a leading […]