Written by Eva-Maria Poptcheva and Andrej Stuchlik (with contributions from Piotr Bakowski, Alexandra Gatto, Detelin Ivanov, Ingeborg Odink, and Irene Peñas Dendariena)

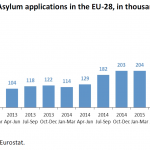

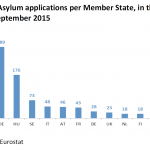

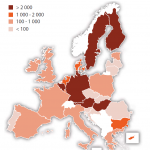

The surge of asylum-seekers to the EU has increased steadily, and reached record highs in recent years and months. Asylum-seekers risk their lives on dangerous journeys to Europe, which often do not stop at the EU’s external border but continue within the EU. In order to prevent asylum-seekers from moving between Member States, and to avoid ‘asylum shopping’ whereby asylum-seekers choose the EU Member State with the highest protection standards for their application, the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), completed in 2013, sought to remove significant differences in treatment of asylum-seekers across the EU, so as to prevent too uneven a distribution of the burden among Member States.

However, asylum-seekers often move to a different Member States than the one in charge of their asylum application according to the so-called Dublin rules, sometimes in the belief that there are better reception conditions in certain Member States, while other reasons such as employment rates and presence of national communities also play an important role.

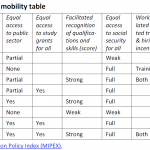

Indeed, EU legislation on the reception conditions of asylum-seekers in the Member States seeks not only to ensure a dignified standard of living for asylum-seekers and beneficiaries of international protection but also, in an EU without internal borders, to prevent secondary intra-EU movements to Member States offering better reception conditions. This has, however, been rendered difficult by the use of directives seeking minimum harmonisation among Member States, which leaves open the possibility to offer more favourable conditions. Furthermore, the provisions on reception conditions standards give Member States the responsibility of deciding the content of the rights afforded, whilst respecting the principle of equal treatment with certain categories of rights-holders in the national context (either nationals or legally resident third-country nationals). This equal-treatment approach is thus based on the protection standards which already exist in individual Member States.

The shortcomings deriving from these differences in reception standards are also relevant in the context of the current initiatives to relocate asylum-seekers from Italy and Greece to other Member States, due to the reluctance of many asylum-seekers to be relocated in Member States in which they believe they will enjoy less favourable reception conditions than in others.

The EPRS In-depth analysis ‘Work and social welfare for asylum-seekers and refugees: selected EU Member States‘ looks at the conditions for access to work and to social welfare for asylum-seekers and beneficiaries of international protection (refugees and beneficiaries of subsidiary protection) in eight EU Member States: Bulgaria, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain and Sweden. The selected Member States are either located at the external borders of the EU, or preferred destinations in asylum-seekers’ and refugees’ secondary intra-EU movements.

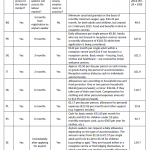

The analysis illustrates that all Member States examined but France have underrun the waiting period of nine months after which asylum-seekers are granted the right to work if there is still no first-instance decision by the competent authority on their asylum application established by the Reception Conditions Directive: six months after the registration of the asylum application in the Netherlands, Poland and Spain, three months in Bulgaria and Germany, two months in Italy, and immediately upon registration of the asylum application in Sweden.

Practical hurdles to the effectiveness of the right to work for asylum-seekers and refugees are common to all Member States, and include lack of knowledge among employers that both groups are allowed to work, insufficient language knowledge, lack of certificates and diplomas to acknowledge specialised skills, as well as asylum-seekers’ residence in reception centres that are often located in remote areas far from economic centres.

The level of benefits provided to asylum-seekers also differs from Member State to Member State. Subsistence allowances depend on whether the asylum-seeker is in a reception centre, whether that reception centre provides food or not, etc. For instance, the monthly subsistence allowance for an adult not accommodated in an reception centre is approx. €347 in Spain, €343 in France, €216 in Germany, €180 in Poland, and €178 in the Netherlands; Sweden provides €227 in an accommodation centre where no food is provided.

A comparison between the social benefits granted to asylum-seekers in the different Member States is difficult to carry out, as countries provide many benefits to asylum-seekers in kind, and the range and value of those benefits in kind is difficult to assess. It can be said that, as a general rule, the differences in the level of benefits provided to asylum-seekers correspond to the differences in living costs among Member States. They also reflect different approaches to social welfare provision.

From an economic point of view, migration flows can contribute to domestic labour markets as they can fill gaps in low and high-skilled occupations; they can address labour market imbalances (some even claim demographic ones), and they can contribute more in taxes/social benefits than they receive. Yet the huge influx of asylum-seekers in 2015 challenges the standard economic paradigm, and above all raises concerns about the costs of migration. Processing and supporting large numbers of asylum-seekers will be costly in the short run, but at the same time offers an opportunity for the EU to revamp its migration policy. Many comparative studies and time-series data suggest that, in the long term, waves of refugees and migrants have had a neutral or slightly positive impact on public finances.

Hence, one of the crucial factors in integrating asylum-seekers is to make labour markets accessible, and to evaluate the ongoing trend of shortening periods for their admission. While reliable data on qualification levels remain scarce, e.g. in Germany, past experience suggests that much potential remains unused and over-qualification is thus an important challenge.

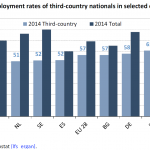

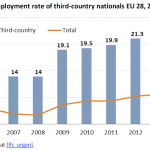

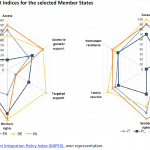

Migrant populations in the EU are more than twice as likely to be unemployed. Another factor in successful migrant integration is the employment rate. In France, the Netherlands, Sweden, and to a lesser degree in Germany, the difference between third-country nationals and domestic workers is more pronounced (up to 28 percentage points) than in Bulgaria, Italy and Poland. The employment rate for third-country nationals in Poland is 65%, and only slightly lower than the total population. As to the institutional framework for integrating migrants into domestic labour markets, those in Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain fare significantly better than those in France, Poland, and Bulgaria. A recent paper comparing Britain and Germany found that with regards to EU migration, the often-claimed difference between contributory and non-contributory welfare states is far less relevant. By contrast, improving administrative and state capacities promise to be more effective.

Finally, the quality of integration of successful asylum-seekers typically hinges upon early and intensive language training, to assess individual skills, to provide easy school access, to address health and social problems, and to engage in dialogue with employers.

Read the complete In-depth analysis on ‘Work and social welfare for asylum-seekers and refugees: selected EU Member States‘ in PDF.

[…] […]