Written by Jan Tymowski,

Equality is one of the fundamental values that the European Union is founded upon, and it is duly reflected in the Treaties, as well as in national laws of the Member States. The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU states explicitly that any discrimination based on – among other grounds – religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation, shall be prohibited. Specific international agreements, such as the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, also prohibit discrimination on various grounds, with limited exceptions in justified cases. The Court of Justice of the European Union has taken this context into account when delivering judgments in specific cases.

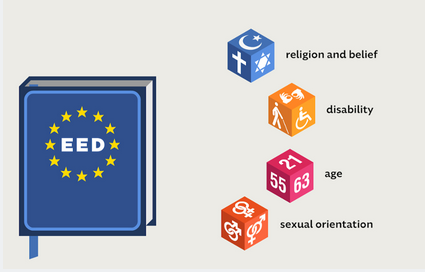

Since employment is a key element in guaranteeing equal opportunities, it was important to indicate in EU law the ways in which discrimination on the relevant grounds should be avoided, prohibited or counterbalanced. In 2000, the Employment Equality Directive (EED) was adopted a few months after the Racial Equality Directive, the EED setting out the minimum rules on discrimination based on religion and belief, disability, age and sexual orientation. Contrary to the Racial Equality Directive, the EED only covers access to employment and occupation, vocational training, promotion, employment conditions and membership of certain bodies. Because of the minimum harmonisation rule, some Member States apply the rules set by the EED also to other areas. A new directive was proposed by the European Commission in 2008 to ensure equal treatment outside employment, but work on this has not yet been completed, especially in the Council.

Although 15 years have passed since the adoption of the EED, equality in employment remains a goal rather than a common fact, and will most likely continue to be dependent on the interpretation of key provisions of the Directive in specific cases. All EU Member States have transposed the basic provisions on four types of prohibited discrimination (direct, indirect, harassment, and instruction to discriminate) into their national laws, with some divergences. Importantly for the effective prevention of discrimination, there is a growing tendency to extend the protection not only to persons who possess the given characteristics (religion or belief, disability, age, sexual orientation) themselves, but also to others – through association or assumption. In addition, prohibition of victimisation should also be extended to other persons – supporting the individual who was or is subject to discrimination.

The principle of non-discrimination on the grounds of religion or belief is relatively new in European law, but has a large reference basis in the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights. In addition to the basic rule of prohibiting direct discrimination, which is relatively easy to apply, there are, and will probably always be, challenging cases of alleged indirect discrimination, where a balance has to be found between, on the one hand, legitimate rules set by employers and, on the other, the fundamental freedom of religion, which includes the right not to hide one’s beliefs. The additional exception provided for in the EED – namely for recruitment purposes of ethos-based organisations – is also subject to critical assessment.

The implementation of non-discrimination because of disability has an established history and practical results, such as physical modifications of the working environment made on the basis of reasonable accommodation. Thanks to the fact that the European Union signed the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, there should be more clarity now with regard inter alia to the definition of disability itself, although precise limitations of this term might evolve further in the future. Case-by-case analysis of proportionality and cost-benefit analysis will surely have an impact on specific measures taken by Member States, employers and other actors, covering also the concept of ‘positive action’ (encouraged by the EED).

Whereas there is no problem with the definition of age, the application of the EED to this grounds for discrimination is almost completely linked to the large exception clause, which permits different treatment (of old or young, or both) when it is well justified by a legitimate aim and achieved by appropriate and necessary means. Apart from the fact that setting the retirement age (for all workers or in special professions) is a national competence, all Member States have multiple, and often very different, provisions regarding restrictions or benefits for young and/or old workers, as well as specific professions. In addition to the need for assessing their coherence with EU law (i.e. whether they truly fulfil the requirements of the EED), the effectiveness of these measures, just as of any positive action also linked to age, is often difficult to prove.

Sexual orientation is the least complicated grounds for discrimination covered by the scope of the Directive, perhaps because the act contains no specific provisions on the matter. On the other hand, it is the least clear in terms of available data, probably due to the less obvious display of characteristics and the intimate aspect of sexual identity of a person. A few judicial cases where discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation was analysed, allowed for the development of concepts that also apply to other grounds (such as ‘association’, ‘assumption’, and ‘harassment’), and the overlap with some religious beliefs contributed to the consideration of multiple discrimination. Notwithstanding the fact that only national laws regulate marital status and related benefits, the practical application of EED led the Court of Justice of the European Union, as well as some national courts, to grant more protection to homosexual couples than previously thought possible.

In addition to the four specific grounds for discrimination, a number of issues important for the effective protection against discrimination are dealt with by the EED in a horizontal manner, and apply equally to all grounds that it covers (religion or belief, disability, age and sexual orientation). This concerns access to information, availability of data, and procedural matters related to judicial proceedings.

Although the perception of discrimination has increased, as shown by the Eurobarometer figures, it is difficult to claim that all people who are victims of discrimination are aware of their rights or that they easily take legal action against discriminatory practices. The EED obliged Member States to ensure the dissemination of relevant information, and a number of initiatives were also taken at European level (including the 2007 European Year of Equal Opportunities for All). Awareness raising campaigns for potential victims and employers alike should be continued, preferably in cooperation with social partners and non-governmental organisations at European, national and local level.

The EED does not require Member States to collect equality data, but the lack of that data constitutes an obstacle in assessing the Directive’s implementation and the state of play with discrimination practices in general. As European citizens are becoming more willing to provide sensitive personal information for statistical reasons, various means could be used to further facilitate the promotion of equality in employment and beyond.

Both in general terms and for individual cases, EU and national regulations, as well as popular awareness of rights, will not result in equality if discrimination cannot be effectively challenged by legal means. In addition to the initial problems with the transposition of the new concept of the burden of proof (where a presumption of discrimination is enough for the accused to be responsible for providing evidence against the charge), national legislation often differs with regard to such elements as time-limits for bringing a case to court, rights of specialised NGOs or equality bodies to actively take part in proceedings, and the level of sanctions. As the EED only contains general requirements in these matters, exchanging best practices seems to be the best way forward, especially through the European Network of Equality Bodies (Equinet).

Overall, the implementation of the EED has a largely positive record, with all 28 Member States having transposed its provisions (mostly correctly) and gained experience in its application. The persisting challenges to its effectiveness are partly related to the fact that, in addition to the general principle of equality and the prohibition of discrimination, specific provisions permit different treatment in justified cases. This requires constant attention and is subject to interpretation on a case-by-case basis (by national or European courts), especially when it comes to such issues as proportionality and the balance of competing rights.

It is up to the European Parliament, among other institutions and actors involved, to consider whether further informative efforts (such as continuous awareness-raising and exchange of practices) are enough to ensure non-discrimination in employment on the basis of religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation, or if additional legislative measures – which would also reflect the implementation of the EED so far – are necessary to achieve the general objective of this Directive – which is the creation of a level playing field as regards equality in employment and occupation in the European Union.

Read the complete Study on ‘The Employment Equality Directive – European Implementation Assessment‘ in PDF.

Video presenting the study

[youtube=https://youtu.be/mQYmPI3DFt0&w=640;h=389]

[…] the study on which this video is based: http://epthinktank.eu/2016/02/10/the-employment-equality-directive-european-implementation-assessmen… […]