Written by Matthew Parry,

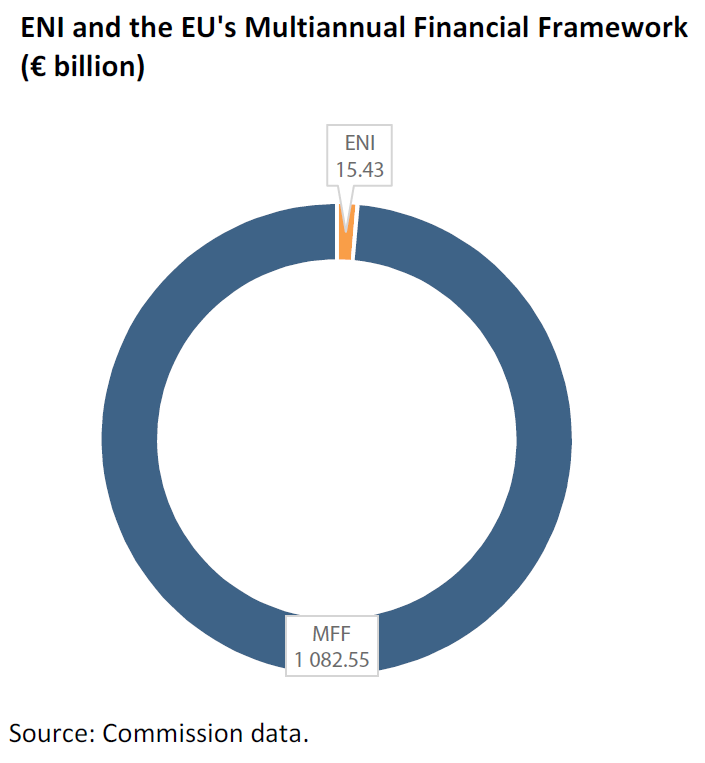

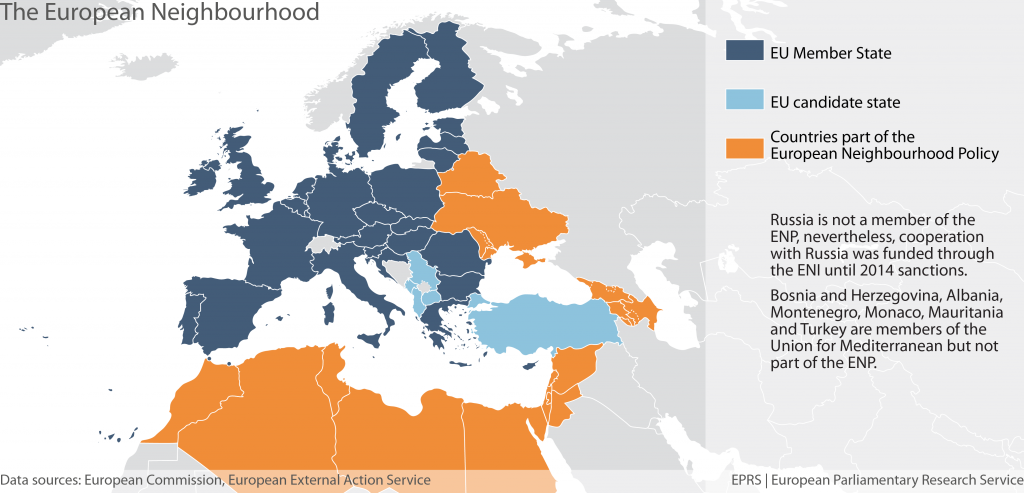

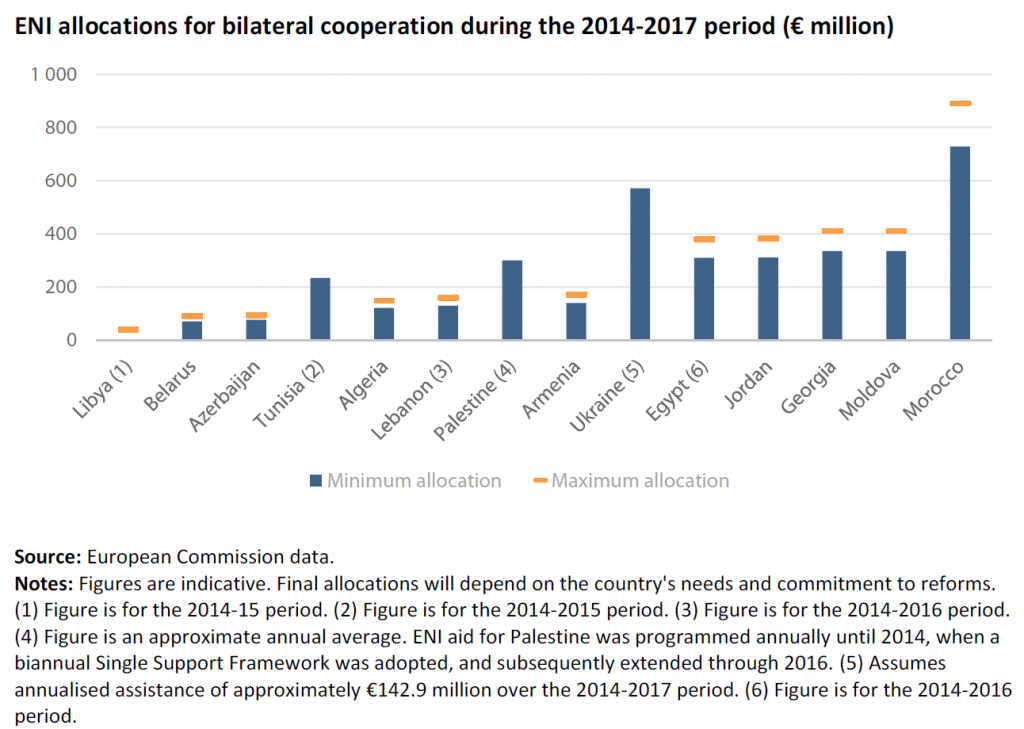

The European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI) was established in 2014 by Regulation (EU) No 232/2014 and endowed with a budget of just over €15.4 billion for the 2014-2020 period. The ENI funds EU efforts to cooperate with and promote development in 16 countries and territories on its eastern and southern frontiers, as part of its European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP). The countries and territories are: Algeria, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Egypt, Georgia, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, the Republic of Moldova, Morocco, the occupied Palestinian territory, Syria (with whose government the EU suspended cooperation in 2011), Tunisia and Ukraine. The idea is that, by incentivising reform in these countries and forging links between them and the EU market, the EU can encourage them to become more democratic, more prosperous and more stable. The EU pursues this objective through bilateral action plans – which should eventually lead to association agreements – negotiated with partner countries and comprising a mix of jointly agreed legal, social and economic reforms supported by ENI financial assistance.

Assessments and audits of projects funded by the ENI and its predecessor for the 2007-2013 period, the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI), carried out by the European Commission, the European Court of Auditors (ECA) and others, cite both examples of best practice and cases where implementation could be improved. For example, the ECA found, in a special report published in September 2016, that projects designed to strengthen public administration in Moldova had merit and had delivered results as anticipated, but that the Commission had not made correct use of conditionality or aligned its approach with Moldova’s own strategic objectives. On the other hand, an ECA special report published in March 2016 singled out a project entitled ‘promoting respect for sub-Saharan migrants’ rights in Morocco’, begun in January 2013 (€2 million) and part-funded by the ENPI, as an example of best practice for setting a limited number of objectives and identifying specific and measurable targets.

Some academics and think-tank analysts have questioned the ENP’s broader rationale of influencing and encouraging reform in countries on the EU’s frontiers with little or no immediate prospect of EU accession. One argues that the ENP, as an attempt by the EU to replicate an approach previously used in candidate countries in the European neighbourhood countries, has had only limited success.

Read the complete Briefing on ‘How the EU budget is spent: European Neighbourhood Instrument‘ in PDF.

[…] […]