Written by Velina Lilyanova,

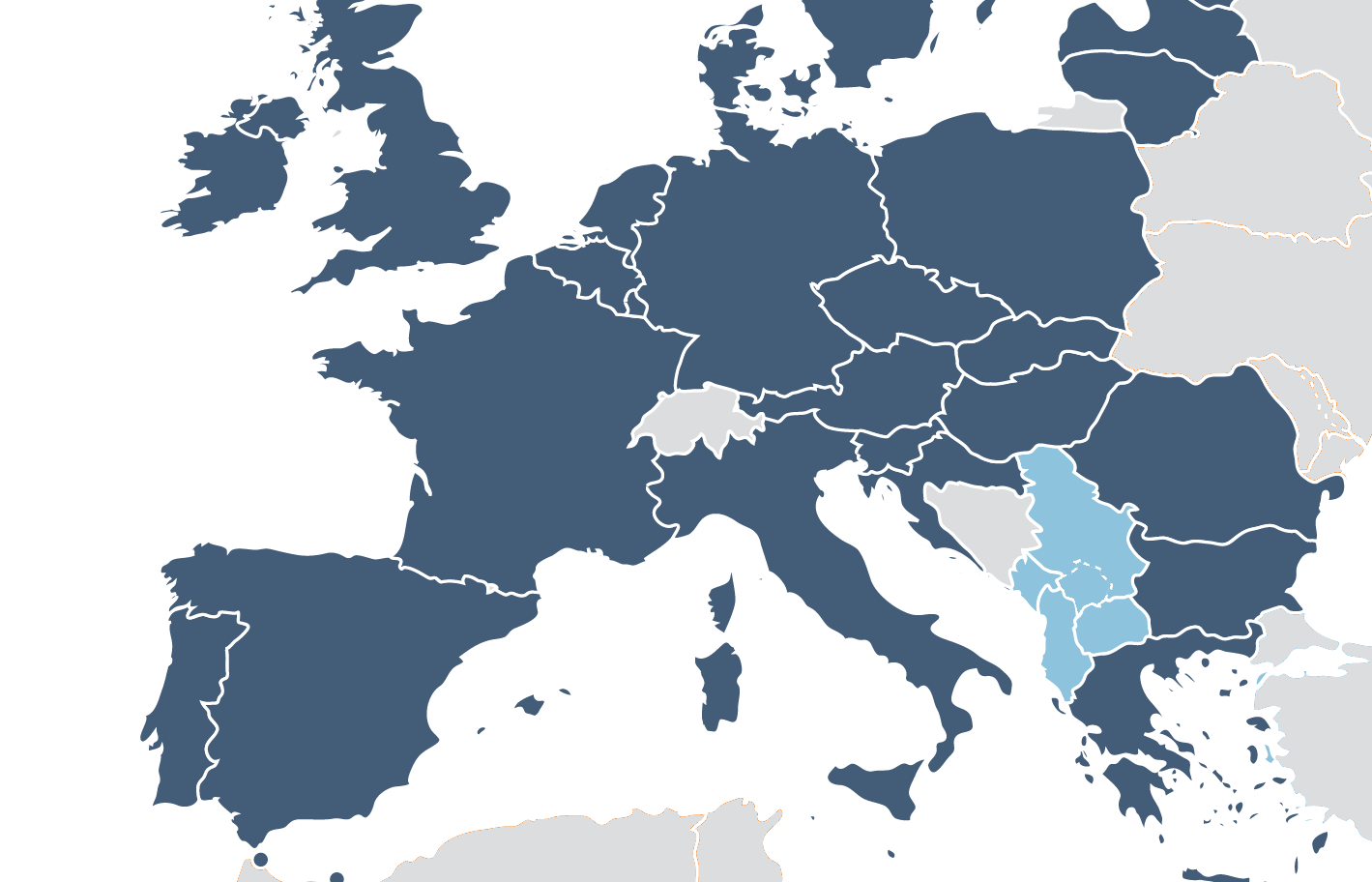

With a resolute tone and a sense of urgency, the European Commission’s new enlargement strategy for the Western Balkans sets a clear direction for the region’s six countries: it offers them a credible enlargement perspective and pledges enhanced EU engagement. It indicates 2025 as a possible enlargement date. However, seizing this opportunity remains a challenge, as the aspirants must each deliver on difficult, key reforms, and solve all outstanding bilateral disputes.

The strategy’s main messages

On 6 February 2018, as a follow-up to Commission President Juncker’s letter of intent to the European Parliament, the Commission published its new enlargement strategy for the Western Balkans (WB). It comes at a time of growing attention to the region and aims to breathe life into the enlargement process, by renewing EU engagement and launching a series of specific initiatives designed to bring tangible benefits to citizens. The strategy acknowledges the WB as a part of Europe that shares history, cultural heritage, challenges and opportunities with the EU, and also the same future. It confirms that a credible accession perspective is a key driver of transformation, and offers the WB a historic window of opportunity, while underscoring the responsibility of the region’s leaders for making a choice and turning it into reality. For the first time, an indicative date for the possible accession of Serbia and Montenegro (as technically most advanced in the process) is set: 2025. The Commission, however, emphasises that this is a target, not a promise, and that the other aspirants could catch up depending on their own merits and rate of progress.

Priority reform areas for the Western Balkan countries

The criteria for EU membership are well established, and while the reform priorities highlighted are not new, the strategy puts them squarely in focus. It outlines three main areas where action needs to be taken without delay. The first is the rule of law: the strategy is explicit when pointing to ‘clear elements of state capture’, ‘links with organised crime and corruption at all levels of government and administration’ and controlled media, among other things. As none of the WB six is considered a functioning market economy, the second area includes addressing structural weaknesses, low competitiveness and high unemployment. As a third area of action the strategy calls for unequivocal commitment to overcoming the legacy of the past through reconciliation and the adoption of definitive binding solutions to all bilateral disputes prior to accession. The stumbling blocks include statehood disputes, and unresolved border, property and social issues. This focus comes at a time when the long (now internal to the EU) dispute between Croatia and Slovenia is again alight.

Montenegro and Serbia are expected to step up efforts to meet the interim benchmarks. For Serbia, forging an agreement with Kosovo and fully aligning with EU foreign policy are key requirements. Albania and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, commended for their alignment with EU foreign policy and their overall progress, expect to open accession talks in 2018. For FYR Macedonia, the main obstacle remains the name issue with Greece, but hopes for resolving it are high. Bosnia and Herzegovina has just submitted its answers to the EU questionnaire aimed at assessing its readiness, and hopes to get candidate status. The strategy is less specific about Kosovo: the country can make sustainable progress by implementing its stabilisation and association agreement, and then forge ahead ‘once objective circumstances allow’.

What the EU has to do

While it is true that the WB carry the burden of the reforms, EU readiness is no less of a challenge. Enlargement would entail costs, have an impact on institutional arrangements and require public support. Hence, the strategy includes a set of actions to be taken later in 2018: launching an initiative to strengthen enforcement of the rule of law; adopting communications on the possibility to enhance the use of qualified majority voting; and stepping up strategic communication. As regards funding, specific provisions for enlargement are to be reflected in the Commission’s proposals for the EU budget after 2020. Special arrangements on the national languages of future EU Member States and irrevocable commitments ensuring that new Member States will not be in a position to block subsequent WB accession, are also planned.

New initiatives and specific measures foreseen

To deliver on the EU’s pledge for greater engagement in the region, the annex to the strategy, an ‘Action Plan in support of the transformation of the WB’, includes six flagship initiatives (Figure 1). Each targets a specific area of mutual interest for the EU and the WB, and envisages concrete actions to be taken between 2018 and 2020. On the rule of law, the Commission plans to enhance the assessment of reform implementation, including through new advisory missions on the ground. On security and migration, it proposes stepping up joint cooperation in fighting organised crime, countering terrorism and violent extremism, and improving border security and migration management.

Socio-economic development would be encouraged by boosting private investment, supporting start-ups, SMEs and facilitating trade, as well as providing more funds for education and health, among other things. More investment is also envisaged for transport and energy connectivity. The digital agenda includes a roadmap to lower roaming costs and to support the deployment of broadband and the improvement of digital skills. The initiative on reconciliation aims to support the fight against impunity and transitional justice, including through setting up a regional commission to establish facts about war crimes. Increasing cooperation in education, culture, youth and sport is also planned. To help implement these initiatives, the Commission has proposed a gradual increase of funds under IPA II until 2020, as far as reallocations within the existing envelope allow.

Reactions to the new strategy

The new strategy was long anticipated and its messages widely welcomed. It has also sparked debate and raised questions both across the WB and the EU. Serbia and Montenegro, singled out as the most advanced in the process, welcomed the document. Serbia defined it as an encouraging message, although President Vučić acknowledged that ‘mountains of obstacles’ lie ahead, most notably the Kosovo issue and border disputes with neighbours. Montenegro, commended for its ‘most notable progress’, also welcomed the document; its prime minister even voiced confidence that it could join the EU ahead of 2025. Albania and FYR Macedonia hailed the positive assessment of their countries’ progress on the European path, and the Commission’s readiness to recommend opening accession negotiations with them shortly. The response from Kosovo has been mixed. While hailing the strategy for treating Kosovo as an integral part of the enlargement plans of the EU, President Thaçi expressed dissatisfaction with it, as, for ‘known political reasons‘ (referring to the non-recognition by five EU Member States), it gives no specific timeframe and clarity on the next steps.

The EU itself is divided over the issue: at the February informal foreign ministers’ meeting, diverging views were expressed on the timetable, either favouring swifter integration or questioning the 2025 perspective. EU leaders are expected to endorse the strategy at the May summit in Sofia and at the June European Council.

Experts welcome the strategy for its clear language and for being more explicit in identifying problems. However, they also point to some gaps and ambiguities that raise questions as to whether the strategy ‘would do enough to change the dynamics in the region’. They commend the strategy for giving bilateral disputes a central place, but less so for remaining vague about possible solutions or about preventing a future veto on enlargement by individual Member States. The highlight of reconciliation, another ‘critically important element‘ of the strategy, is also welcome. In that respect, concerns have been expressed that the strategy is rather ‘aspirational’ and fails to concretely address past grievances still undermining the prospects for peace.

Read this At a glance note on ‘Western Balkans: Enlargement strategy 2018‘ on the Think Tank pages of the European Parliament.

Reblogged this on World Peace Forum.

[…] Source Article from https://epthinktank.eu/2018/03/14/western-balkans-enlargement-strategy-2018/ […]