Written by Gisela Grieger (updated on 16.12.2019),

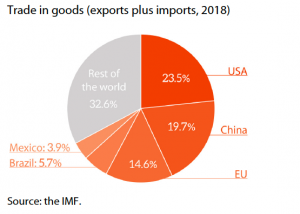

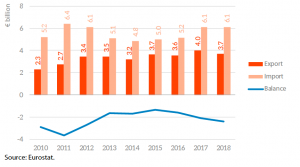

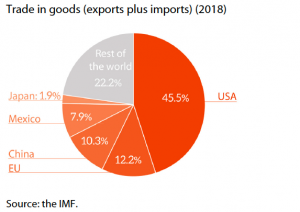

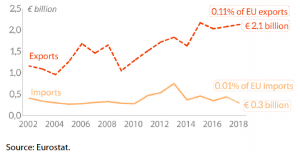

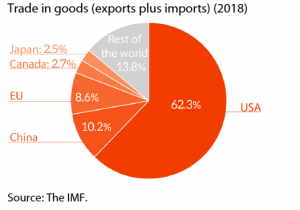

The 33 countries forming the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) taken together have remained the EU’s fifth largest trading partner and constitute a region with which the EU maintains close cooperation and political dialogue on account of its historical, cultural and economic ties. However, as a consequence of global power shifts and of Asian markets having become the drivers of global trade, in the past two decades the EU has lost significant market share in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), mainly to China.

As the rules-based multilateral trading system has come under severe strain in the face of an unpredictable US trade policy geared towards protectionist bilateralism and unilateralism, the EU’s major LAC negotiating partners, such as Argentina and Brazil in the aftermath of the 2015 and 2018 presidential elections, have renewed their commitments to multilateralism and free and fair trade. This provided a window of opportunity for the EU to conclude an EU-Mercosur ‘agreement in principle’ in June 2019, and to reassert its geo-economic and geo-political interests in the region ahead of the October 2019 elections in Argentina, the outcome of which may jeopardise Mercosur’s ambitious trade liberalisation agenda.

In 2018 and 2019, the EU has made major headway towards achieving three objectives of its 2015 Trade for All strategy as far as LAC is concerned: 1) in April 2018, an ‘agreement in principle’ on a modernised trade pillar of the EU-Mexico Global Agreement was reached; 2) in 2019, EU-Chile negotiations on a modernised trade pillar of the EU-Chile Association Agreement gained new impetus; and 3) on 28 June 2019, after 20 years of negotiations an ‘agreement in principle’ was reached with the four founding members of Mercosur – Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay – on the trade pillar of a broader EU-Mercosur Association Agreement. The latter may be seen as a breakthrough from a geopolitical and trade standpoint. However, it has sparked controversy between those rejecting it for the assumed adverse impact of its trade pillar on sustainable development, climate change, small-scale farming and the rights of indigenous peoples, and those advocating leveraging its trade pillar to foster sustainable policies in Mercosur countries so as to halt the massive deforestation of the Amazon and to push vigorously for decisive steps to be taken for large-scale reforestation.

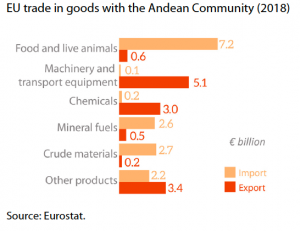

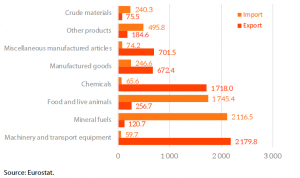

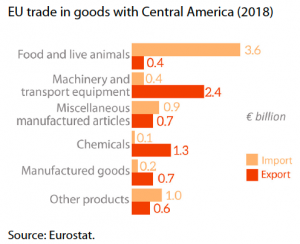

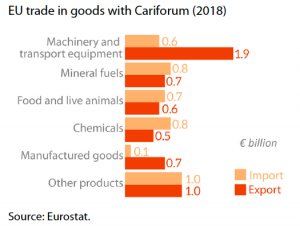

The ‘agreements in principle’ and the ongoing talks with Chile build on an EU strategy pursued since the 1990s of promoting sub-regional integration within LAC and bi-regional integration between the EU and the four sub-regional LAC groupings (the Andean Community of Nations (CAN), Cariforum, the Central America group, and Mercosur), and bilateral integration with Chile and Mexico. This strategy resulted in agreements governing trade relations, including fully fledged agreements with two sub-regional groupings (Cariforum and Central America), a multiparty free trade agreement (FTA) with three countries of the Andean Community (Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru) and bilateral agreements with Mexico and Chile.

Overall, the EU’s agreements governing trade relations with LAC differ considerably in terms of coverage and methodology, depending on the time at which they were concluded and the context of the negotiations. The trade pillars of the existing trade agreements are less comprehensive and advanced in terms of liberalisation compared with the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). They lack, inter alia, specific provisions on sustainable development (which are covered in softer political dialogues) and have limited World Trade Organization plus (WTO+) provisions on intellectual property rights (IPR), services, investment, public procurement and regulatory cooperation.

The 2019 resolutions of the European Parliament (EP) on the implementation of the EU’s FTA with Colombia and Peru and of the trade pillar of the EU-Central America Association Agreement have stressed that much more work needs to be done to increase the uptake of preferential rules on both sides (notably by better supporting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and to ensure that civil society is empowered significantly to make a meaningful contribution to strengthening the enforceability of the commitments made in the trade and sustainable development (TSD) chapters. Unlike the policy pursued by the European Commission, the EP resolutions do not exclude the use of sanctions as a last resort.

Read the complete in-depth analysis on “EU trade with Latin America and the Caribbean: Overview and figures“.

[…] EU Trade With Latin America And The Caribbean: Overview And Figures […]