Written by Jana Titievskaia, Carla Stamegna, Vadim Kononenko, Cecilia Navarra and Klemen Zumer,

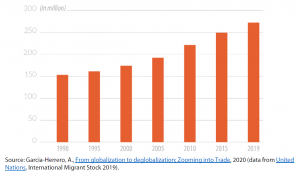

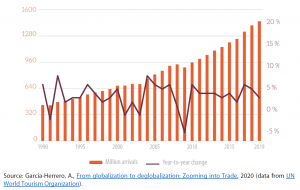

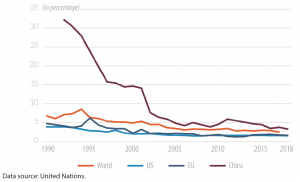

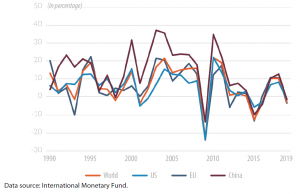

The period from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the global financial crisis of 2007 marked an era of fast-growing interdependence between different economies and cultures, brought about by cross-border movements of people, goods, services, capital and data. Far from being the first ‘globalisation’ wave, it is considered to be a period of ‘hyperglobalisation’. The decade which followed the financial crisis of 2007-2008 was marked by a slowdown in global interconnectedness. In 2019, the term ‘slowbalisation’ spread, to signify the waning of globalisation as we know it. For instance, international trade and investment relative to gross domestic product (GDP) started to decline. Supply chains began to contract after years of global outsourcing and offshoring. In terms of international cooperation and multilateralism, the pace of the world’s economic integration waned. For some governments, notably the Trump administration in the United States of America (USA), it is no longer evident that international institutions such as the World Trade Organization or the World Health Organization are fit for purpose. Rising nationalist and populist leaders in several parts of the world began questioning the ideological doxas of globalism and, in some cases, neoliberalism. Nevertheless, globalisation in other areas, such as international data flows, migration and tourism, continued to expand, indicating that perhaps globalisation was merely changing shape. In 2020, the coronavirus pandemic dealt a profound shock to global trade, investment and travel. The disruption to the physical movement of people, goods and services brought about by the pandemic has been so severe that the thesis of ‘slowbalisation’ merits thorough analysis.

Globalisation has been evolving over time, becoming increasingly complex and multi-faceted. In this paper, five pathways of globalisation have been selected to illustrate the contrasting ways in which global integration has been slowing down, accelerating or continuing. Each exhibits a different development pattern:

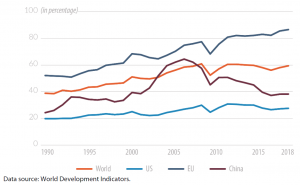

- Cross-border trade in goods and services slowed in terms of volume and relative to GDP, in spite of record low average tariffs. This slowdown can be traced to variation in supply chains, accounting principles, escalating protectionism, and most recently Covid‑19.

- Global financial openness slowed after the financial crisis in terms of cross-border capital flows and bank lending. However, international regulatory cooperation in the realm of global finance continued to increase, only recently showing a trend towards some reversal.

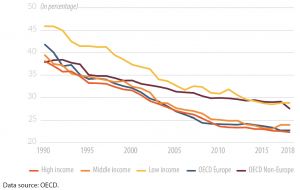

- Deepening inequality has been a by-product of hyperglobalisation, has continued during the slowbalisation phase, and is likely to continue after Covid‑19. The causes are rooted in government policies affecting income distribution, including taxation and the strength of multinational corporations.

- Globalisation of social interactions, reflected in rates of tourism and migration, did not slow until the sudden arrival of the Covid‑19 pandemic.

- International digital exchanges, measured by cross-border data flows, have continued expanding throughout the ‘slowbalisation’ period. Social distancing and restrictions on international travel are likely to accelerate globalisation in the digital realm.

As a result of the Covid‑19 crisis, the future could be one of patchy globalisation, characterised by more immaterial exchanges, and posing further challenges to the future of global governance and international cooperation. The EU could lead the way towards a more sustainable and considered form of globalisation in each of these realms.

Read the complete ‘in-depth analysis’ on ‘Slowing down or changing track? Understanding the dynamics of ‘Slowbalisation’‘ in the Think Tank pages of the European Parliament.

[…] […]