Written by Alessandro D’Alfonso, Angelos Delivorias, Nora Milotay and Magdalena Sapała,

Growth in gross domestic product (GDP) in Europe collapsed in 2020 as a result of the economic crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Moreover, in contrast with previous recessions, the uncertainty caused by the pandemic also caused a shift in consumption and investment patterns. In great part thanks to the discovery of effective vaccines against the virus, GDP growth is expected to rebound in the coming two years. This forecast depends on several variables, however, including the length and size of the support programmes put in place by governments and central banks, geopolitical tensions, and the future relationship between the European Union and the United Kingdom.

When it comes to employment, the positive trends observed in previous years were reversed in 2020 as a result of the economic crisis. The picture would have been bleaker had it not been for various support schemes and policy measures at national level, supported by a number of measures at EU level, and the EU’s new SURE instrument for temporary support to unemployment schemes. Nevertheless, interpretation of the numbers must be nuanced, given that many unemployed people were pushed out of the labour force in 2020, hiding the full effect of the economic crisis. Moreover, future unemployment figures will depend on the timing and pace of the withdrawal of policy support schemes and on whether the economic recovery has materialised by then. Taking these factors into consideration, unemployment is expected to increase in 2021, and then decrease slightly in 2022.

General government deficits are expected to have increased significantly, as a result of the various fiscal measures put in place to counter the economic crisis. Deficits are expected to decrease from those highs in the next two years, but still remain over the 3 % limit set by the Maastricht Treaty. Similarly, the debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to increase significantly in 2020, both for the euro area and for the EU as a whole, and to continue increasing slightly in 2021 and 2022.

Lastly, in 2020, inflation for the euro area was slightly above zero and, despite picking up in the next two years, is still expected to remain below the target of 2 % set by the European Central Bank. In this context, but also to support the Member States, the ECB maintained its asset purchase programme (APP), launched a new one for the duration of the pandemic, and extended its accommodative measures.

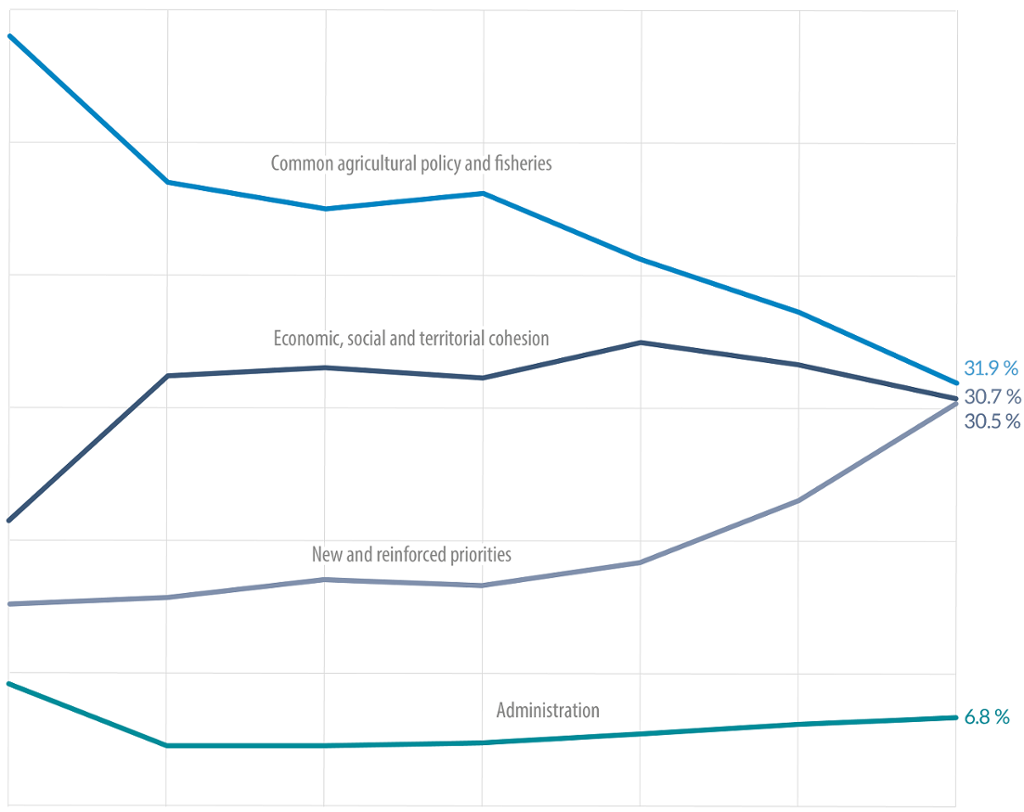

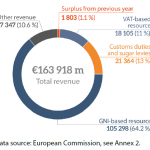

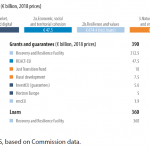

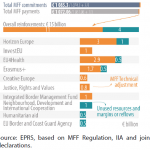

The coronavirus pandemic influenced the negotiations on the medium-term architecture of EU finances, which resulted in the adoption of an unprecedented budgetary package in December 2020. This combines the €1 074.3 billion multiannual financial framework (MFF) for the years 2021 to 2027 with the €750 billion Next Generation EU (NGEU) instrument. The agreement brought new momentum to the EU budget, assigning it a major role in the Union’s strategy to relaunch the economy. The launch of NGEU, a temporary recovery instrument (2021-2023), to be financed through resources borrowed on the markets by the European Commission on behalf of the Union, is a major innovation.

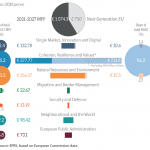

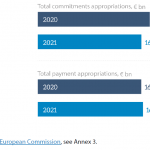

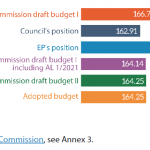

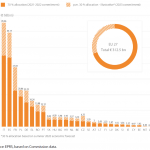

The 2021 budget is of a transitional nature. As the first under the new MFF, it shows the amounts needed to launch the new generation of EU actions and programmes, but also provides the payment appropriations needed for the closure of the programmes relating to the 2014-2020 MFF. Furthermore, NGEU will significantly increase the resources channelled through the 2021 EU budget, adding an estimated €285.15 billion in commitments and €75.93 billion in payments to selected programmes. As a result, in 2021, total commitments will almost triple the usual annual expenditure of the EU budget. While investment in recovery and resilience measures is the overarching priority of EU spending in 2021, the EU budget will continue contributing to the achievement of other objectives, in such areas as the green and digital transition, cohesion and agriculture, security and defence, migration and border management, and the EU’s role in the world.

Social and employment policies are strongly interlinked with other major policy fields, most importantly the economy, the public health system and education. Social considerations are also part and parcel of all policy fields – also set out in Article 9 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union – and are woven into the fabric of society, directly affecting people’s everyday lives. The coronavirus outbreak and lockdown measures have caused major disruption, and exacerbated existing social risks and challenges, such as: an ageing population; rising inequalities between socio-economic groups, generations, genders and regions; new forms of work; and greater polarisation of wages between higher and lower paid workers. This situation is threatening to increase the divergence between Member States, and regions, making achievement of one of the main EU objectives, (upward) social and economic convergence, more difficult. Moreover, it again raises issues around the sustainability of public finances. Therefore, there is an even greater need than before to update the EU’s welfare states and labour markets, which implies structural changes in many instances.

Given the complexity of the issues that social and employment policies have to tackle, the EU has a broad range of tools available to design and support the implementation of policies in the Member States. These range from setting minimum standards and targets, and providing policy guidance and funding, to the EU’s economic governance mechanism. Beyond the immediate response to the crisis, the EU intends to contribute to nurturing more systemic resilience across the board, to enable Member States to bounce back, or even forward, from shocks in a sustainable way, to preserve the well-being of all of the EU’s population.

Close to three quarters of the funding programmes within the multiannual financial framework (MFF) for 2021-2027 and most of the investments through the new instrument, NGEU, can be used to support the implementation of policies that could contribute to the update of welfare states and labour markets. However, due to the relatively small size of the MFF compared to national budgets, its main function is to incentivise transformation and innovation on the ground that – in the longer term – can lead to systemic change. For that reason, the way the MFF, combined with other EU policy tools, shapes both the quantity and quality of spending (i.e. governance mechanisms and institutions on the ground) matters equally. This time, NGEU is designed to give an additional boost to the resources channelled through EU budgetary instruments and strengthen their pull for investment into relevant fields. Both new and old instruments seek to open avenues for increased solidarity among Member States based on common borrowing, and to promote a social investment approach to financing. In addition, through its other policy tools, including setting objectives and targets, the EU can help Member States to develop the necessary structures and institutions that in turn can help them absorb the increased funds more efficiently.

Read the complete study on ‘Economic and Budgetary Outlook for the European Union 2021‘ in the Think Tank pages of the European Parliament.

[…] […]

[…] Economic and Budgetary Outlook for the European Union 2021 […]